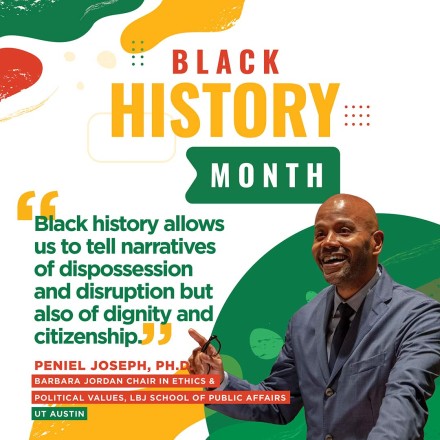

Peniel E. Joseph, Ph.D.

Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values, LBJ School of Public Affairs

UT Austin

A professor of History and Public Affairs, Dr. Joseph is also the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values among other notable titles he holds at UT Austin. His book, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.,” published in 2020, recently received the UT Austin Hamilton Book Grand Prize, the university’s top award for books published by faculty. He is a frequent commentator on issues of race, democracy and civil rights. His career focus has been on “Black Power Studies,” and he has authored multiple other award-winning books. He is a Life Member of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, a Fellow of the Society of American Historians and a contributing writer for CNN.com.

As we celebrate Black History Month, who is a personal hero of yours, and what impact has that person made on your life?

I would say that both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. have been two of my personal heroes. In fact, they are the subject of my book, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” From Malcolm, I learned about the value of dignity. The fact that we are all endowed by our creator and, by existing, human dignity transcends all boundaries and systems and structure of oppression. Malcolm’s notion of Black Radical Dignity transformed Negroes into Black people during the Civil Rights and Black Power eras and continues to resonate today. From Dr. King, I have learned to better appreciate the value of citizenship. King defined citizenship as more than simple civil and voting rights. He argued that true citizenship meant a guaranteed income, food security, racial integration and safe neighborhoods, schools and communities, and freedom from violence, racism and poverty. The book’s title refers to our contemporary misunderstanding of the legacies of Malcolm and Martin; we think of Malcolm X as the political sword and King as the nonviolent shield. In fact, they were both. Malcolm’s call for human rights made him Black America’s prime minister, traveling to Africa and the Middle East calling for an end to colonialism abroad and racism at home. King’s opposition to the Vietnam War, break with the mainstream establishment and organization of a massive Poor People’s Campaign announced him as a critic of war, economic injustice, racism and imperialism.

In July 2020, CNN published your column, “America is on a brink like none since the Civil War.” In it, you contend that year ushered in the most dynamic social movement for racial justice in American history in response to the killing of George Floyd. What did you mean by “on a brink,” and how would you describe the state of that movement today?

The Black Lives Matter ferment that catalyzed in the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s death in 2013 continues today. BLM 2.0 in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder inspired the largest mass social movement in American history, one with global reverberations. Since that time, we have been locked in a cycle of racial progress and backlash. In many ways, what that essay referred to is the narrative war between Reconstructionists and Redemptionists that characterizes American history since 1865. It is the subject of my recent book, “The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century.” Reconstructionists are supporters of multiracial democracy, and redemptionists are advocates of white supremacy and the Lost Cause. The searing juxtapositions of 2020 – the racial inequality of the pandemic response; the police killings of Black people; the rise of BLM and movements that stood in solidarity, especially white Americans who marched and protested for racial justice; the defeat of the MAGA movement and Donald Trump; the election of the first Black and Jewish senators from Georgia on Jan. 5, 2021, followed by the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection and everything since, are all rooted in this narrative war surrounding what kind of nation we are going to be. The notion that America stood on the brink remains true. Democracy remains imperiled by voting suppression; freedom of speech under siege by anti-CRT legislation; the basic rights of citizenship and body autonomy attacked via the Dobbs decision and the undermining of reproduction justice; and police killings of Black people remain a national tragedy as witnessed by the recent death of Tyre Nichols in Memphis.

The theme of this year’s Black History Month is Black Resistance, which explores how “African Americans have resisted historic and ongoing oppression, in all forms, especially the racial terrorism of lynching, racial pogroms and police killings," since the nation's earliest days. How does Black Resistance relate currently?

Black Resistance is reflected in efforts to share a deeper, more complex and challenging history of the nation. I attempt to do this in “The Third Reconstruction.” Nikole Hannah-Jones’ “The 1619 Project” on Hulu is a great place to witness this. That project, which began as a Sunday The New York Times Magazine special issue has grown into the most impactful piece of writing on race and democracy ever conceived. It’s that powerful and has inspired controversy as something that is anti-American. I could not disagree more. In telling the story of how Black Americans have stood at the forefront of the nation’s democratic story, despite slavery, Jim Crow and state-sanctioned violence, Hannah-Jones has written a tough love letter to the nation. “The 1619 Project” is deeply reverential of the American dreams of Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, Francis Harper, Ana Julia Cooper, W.E.B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Martin and Malcolm, and Stacy Abrams, Ayo Tometti, Alicia Garza and others who have struggled, organized and faced punishment, harassment and even death to tap into what King characterized as “those great wells of democracy” in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“The 1619 Project” is a Black history and Black Studies Project. Black Studies is the interdisciplinary investigation of the entire African Diaspora — its connections to Europe and the Americas (Central, South, North, the Caribbean) and the entire world in the making of modernity and its successes and discontents. Black history allows us to tell narratives of dispossession and disruption but also of dignity and citizenship. It panoramically deploys fields such as history, sociology, anthropology, women’s studies, queer studies, political science, law and society, cultural criticism, film studies and more to delve into the origin story of our time and gives us ballast to move forward and build what Martin Luther King Jr. characterized as the “Beloved Community” free of racism and economic injustice.

Telling what King characterized as the “bitter but beautiful” struggle to make Black dignity and citizenship a reality is at the heart of Black history’s calling and what at times makes it so controversial. Ultimately, Black history inspires us to recognize the freedom movements born out of the nation’s original sin of racial slavery represent the beating heart of American democracy and far from dividing us, have the potential to build consensus around an American identity based on Reconstruction impulses that see the value and integrity of multiracial democracy.