Rabbi Maurice Faber

Appointed by

Term

Occupation

Date of Passing

Notes

Excerpt from "The Mixers: The Role of Rabbis Deep in the Heart of Texas," by Hollace Ava Weiner; American Jewish History, Vol. 85, 1997. Retrieved from web on September 11, 2006.

Zielonka's El Paso years parallel the Texas career of Rabbi Maurice Faber. Faber arrived in the summer of 1900, invited by a congregation impressed with reports of a patriotic speech he had delivered to a Midwest gathering on the US Constitution. Born in Hungary in 1854, Faber often remarked that "he was more of an American than those who chanced to be born here because he was `an American by choice.'"(174) Faber, the descendant of a long line of rabbis, rejected the orthodoxy of his forebears. Although his father had no use for the movement, the younger rabbi embraced Reform Judaism. The ideological break between father and son proved irreparable. Ordained in 1873, Faber departed Hungary in 1879 for the United States. He found a part-time pulpit in Titusville, Pennsylvania, at Congregation B'nai Zion, a Reform synagogue with a dozen families. In 1898 he moved to Keokuk, Iowa, a Mississippi River congregation with a grandiose Reform synagogue founded in 1856 and a proud history as Iowa's oldest Jewish congregation. Unfortunately, Keokuk, which called itself Iowa's Gate City, was past its prime. Steamboats were outmoded; the railroad had bypassed the town; the congregation, with 21 families, including 13 students, was drying up.(175) When Tyler, Texas, advertised for a rabbi two years later, Faber eagerly applied.

Tyler's legacy and landscape evoked not the Western cowboy but the Deep South. Seventy-five miles from Louisiana, Tyler had served as a supply base for the Confederacy because of its bountiful harvests and natural forests that produced mints, berries, sweetgum, sassafras and a wealth of pharmaceutical ingredients.(176) The countryside's rolling, sandy loam hills later made it a rose-growing capital with annual flower pageants, parades, Southern belles, and balls. By 1900 three colorful governors and one US senator had hailed from Tyler, a county seat with 30,000 inhabitants and about 100 Jews, many of them retailers in business around the town square.(177) Faber, with his bellowing voice and strong opinions, fit into the political mix. He chaired town hall meetings, snared land and funds for a Carnegie public library and raised money to feed handicapped children at home and to purchase matzoh for an impoverished Talmudic academy in Prague.(178) When Faber delivered a high school commencement address for 95 graduating seniors, 1,200 people jammed the auditorium to savor his words.(179)

Faber was chaplain at Tyler's St. John's Masonic lodge, which dated to 1849. When Ku Klux Klansmen infiltrated the 500-member lodge in 1915 they insisted that new Masonic lodge members apply simultaneously for membership in the Klan. The rabbi led a faction of lodge members in opposition. The dispute led to a state Masonic investigation and a 10-month suspension of the St. John's charter. Over the next several months, a breakaway lodge of 65 men formed with Rabbi Faber installed as chaplain and listed among the officers. With the agreement of the new lodge, the St. John's charter was restored. A decade later, during hard economic times, a resolution to merge the two bodies failed. (180)

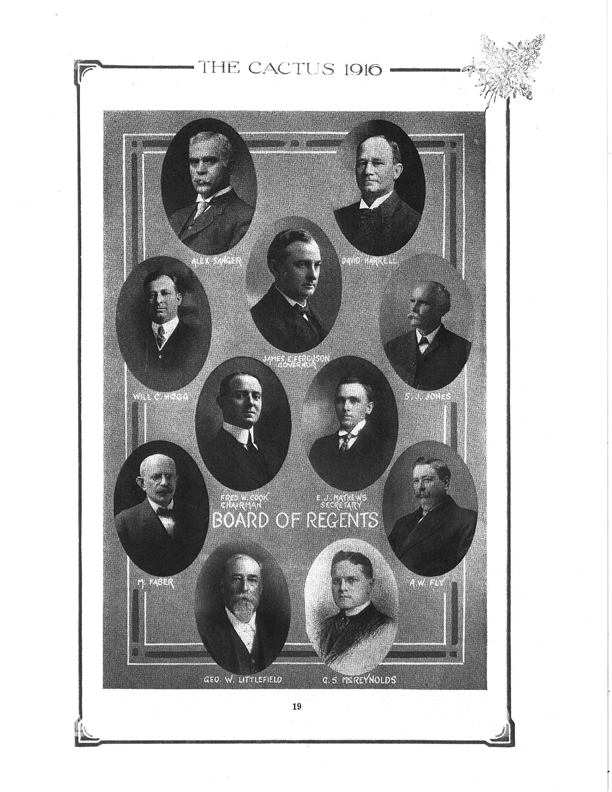

A decade before the Masonic split, Faber's bearing and prestige led a local politician to recommend that the governor appoint the rabbi to the University of Texas Board of Regents. Faber, the first clergyman to sit on that board and its second Jew, was amused when the certificate naming him a regent identified him as "Father Faber." The governor, James "Pa" Ferguson, was a school dropout and a Methodist preacher's son with little inkling of Judaism. A populist elected by "the boys at the forks of the creeks," the governor likewise had no hint of the rabbi's intellectual independence.(181) Accustomed to selling prison pardons and dispatching state employees to buy cattle for his ranch, the governor also maneuvered to run the university. He targeted for dismissal six faculty and one staff member who had criticized his administration or become involved in political crusades with which he disagreed. One of the objectionable professors, the head of the journalism department, owned a newspaper that "skinned the governor from hell to breakfast."(182) Another, a physicist, crusaded against the state capital's red-light district, focusing disrepute on the capital city of Austin. A third, famed folklorist John A. Lomax, published cowboy song lyrics the governor derided as too lowbrow for an academician. ("When I die, don't bury me at all. Just pickle my bones, in alcohol.")(183) Some of the faculty appeared to have overcharged the university for mileage expenses. Ferguson branded the whole lot of them "butterfly chasers."(184) He wrote the rabbi expecting his vote to oust them. The rabbi balked.

In September, 1916, Faber wrote the governor: I never dreamed that ... the appointee is expected to be a mere marionette to move and act as and when the Chief Executive pushes the button or pulls the string ... I cannot pledge myself to follow the arbitrary will of any person, no matter how high and exalted, without being convinced of the justice of his demands. In my humble opinion such course will disorganize and disrupt the University, the just pride of the people of Texas.(185)

The governor responded, threatening to remove Faber from the board:

I do not care to bandy words with you further. ... I shall not hesitate to repair the wrong which I have done in appointing you.... You are defying your friends and proving yourself culpably disloyal by aligning yourself with a political ring in the University who, if permitted to continue, will cause the people sooner or later to rise up and disown the whole affair.(186)

The pair's peppery correspondence--printed in Texas newspapers and introduced into evidence during the governor's impeachment trial in July 1917--turned Faber into an icon of academic freedom. Letter writers lauded Faber as an "American citizen and patriot who understands the genius of our government and reveres its institutions." The governor was reviled as an "ass," prone to braying in public and private.(187) Wrote Austin's Episcopal Reverend Y. H. Kinsolving of the rabbi: "King Agrippa said to St. Paul: Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian. I say to you: Almost thou persuadest me to be a Hebrew."(188)